By Emma Ash

We are all guilty, we ought all to plead guilty, and not to exculpate ourselves by throwing the blame on others.

William Wilberforce, House of Commons, 1789.

Trigger Warning: This piece includes historical documents, which may be distressing for some readers.

In June this year, I was honoured to be part of a group granted private access to a temporary, specially curated exhibition at St. John’s College, Cambridge, where many of the most powerful abolitionist documents and artefacts from British history were laid out before us; some rarely seen by the public.

This was no ordinary college tour. We stood before letters written in the hand of William Wilberforce, pored over Thomas Clarkson’s field notebooks, and stared in disbelief at illustrated evidence of the horrors enslaved people endured. These materials weren’t simply relics of a past age, they were acts of resistance, proof of how advocacy, research, protest, and writing changed the course of human history.

What follows is an account of the exhibition, weaving together political speeches, investigative diaries, haunting images, and commemorative tokens, all rooted in a place that continues to inspire critical thought and moral action.

Parliamentary Bill

Though the exhibition opens with the landmark 1807 Parliamentary bill proposing the abolition of the slave trade, a powerful symbol of justice finally passed in law, it’s the documents that came before it that reveal the decades of resistance, research, and moral courage required to reach that moment. This document laid the groundwork for a moral revolution to be transformed into legal reform. It was people like Thomas Clarkson, a former theology student at St. John’s, and William Wilberforce, MP for Yorkshire, who tirelessly pushed to turn public sentiment into parliamentary action.

Photo by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

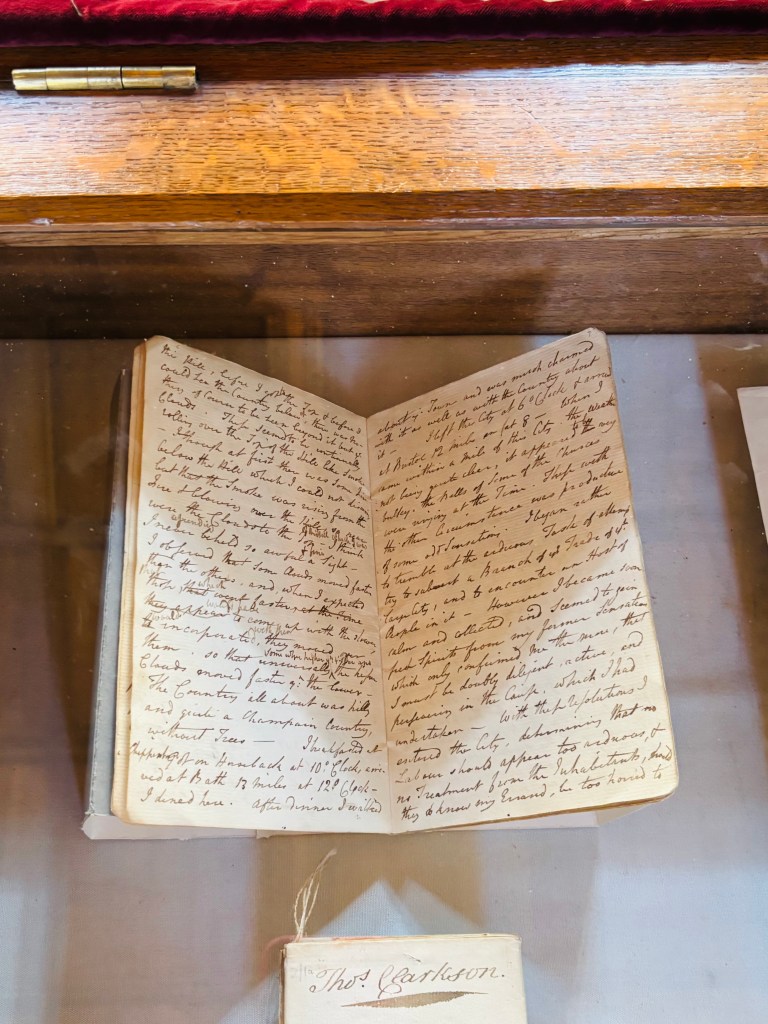

Thomas Clarkson’s Abolitionist Journal

Next, we viewed an extraordinary primary source: Thomas Clarkson’s handwritten journal, used while he travelled across Britain investigating the transatlantic slave trade. This was no academic exercise, Clarkson boarded slave ships, examined shackles, and interviewed sailors. His notebooks documented first-hand evidence of cruelty, later used to build legal and moral arguments in Parliament. This journal is a rare witness to history, the raw, immediate thoughts of a man who devoted his life to justice.

Photo by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

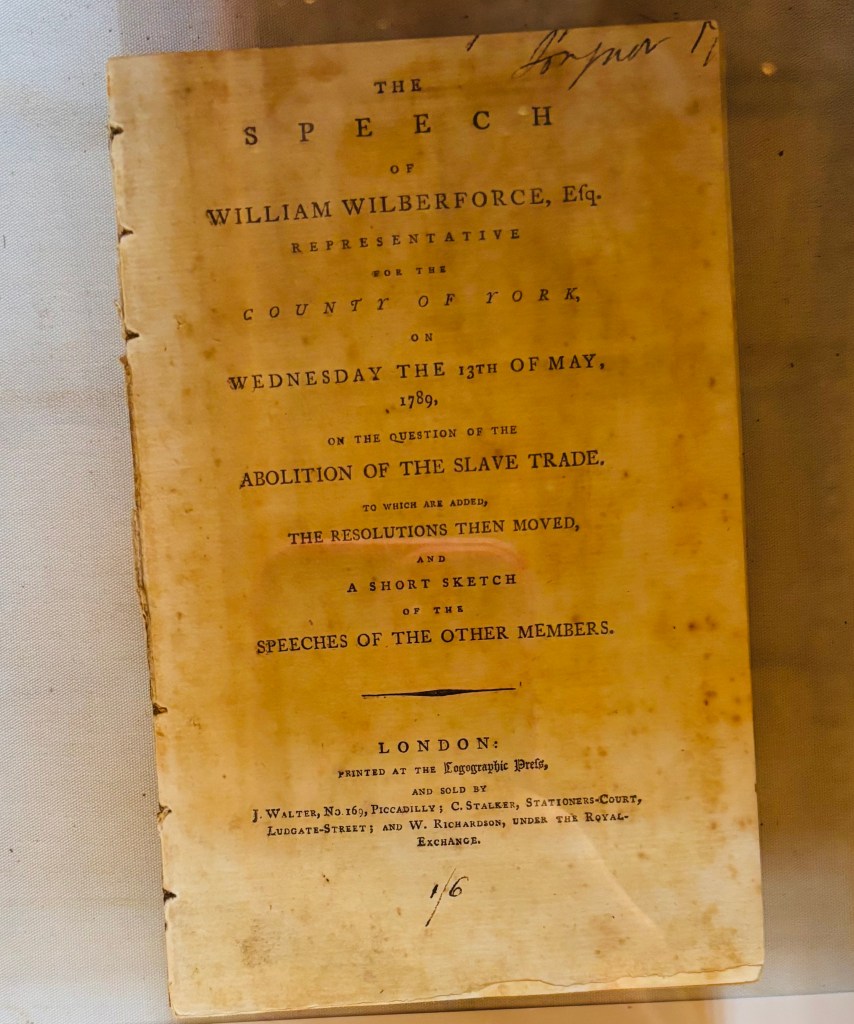

The Speech That Shook Parliament: Wilberforce, 1789

Wilberforce’s now-famous speech of 13 May 1789 was also on display in pamphlet form, distributed widely at the time. Drawing on Clarkson’s research, Wilberforce called on MPs to recognise the trade’s inhumanity. Though Parliament wouldn’t vote to abolish the trade until 1807, this speech was a seismic moment. Seeing it in person reminded us that words, when spoken with courage and conviction, can become instruments of change.

Photo by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

Wilberforce’s Letter to Lord Henry Petty

In a letter dated 19 February 1807, just weeks before the Slave Trade Act passed, Wilberforce wrote to Lord Henry Petty advocating for Clarkson’s appointment as Professor of Modern History at Cambridge. This piece, recently sold at auction in 2023. It reminds us that abolition wasn’t only about public speeches; it was also about institutional influence.

Photo by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

List of Mr. John Broomfield’s Negros with their Age & Valuation

One of the most shocking items that we encountered was a valuation list of enslaved people titled “List of Mr John Broomfield’s Negros with their Age & Valuation.” Each line listed an individual’s name, age, financial worth, and occupation, reducing human beings to a ledger of assets. These kinds of documents expose the raw economic underpinnings of slavery, how lives were itemised for ownership, inheritance, and trade. It was a confronting reminder that for many, the horror of slavery lay not only in violence, but in erasure of humanity.

Photo by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

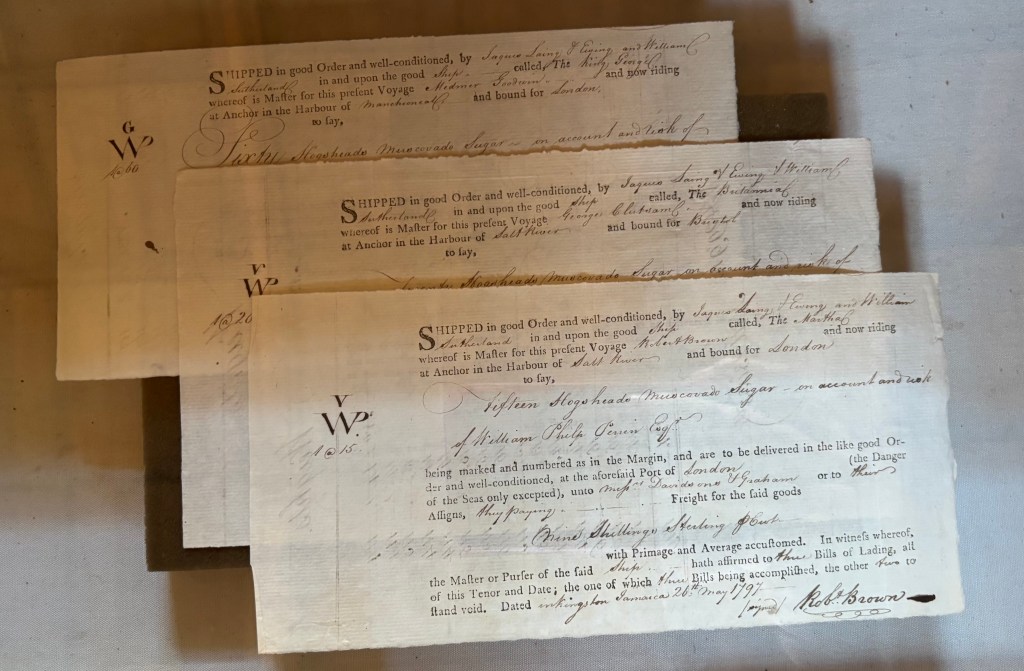

Transportation Documents

Adjacent to the valuation list was a set of transportation documents which, at first glance, appeared deceptively routine. Closer examination revealed the bureaucratic language that facilitated and legitimised the trafficking of human beings. These documents underscore how the transatlantic slave trade operated not only through overt violence, but also through systematic administrative processes that normalised and obscured its inherent atrocities.

Photo by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

The Horrors Made Visible: Illustrated Poster from 1843

By the 1840s, abolitionists turned increasingly to visual propaganda to stir public emotion. The poster we saw, titled “The Horrors of Negro Slavery,” was published in The Pictorial Times in 1843.

Photo by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

Slave Ship Diagram

The infamous slave ship diagram was published by British abolitionists to expose the dehumanising conditions of the Middle Passage. Enslaved Africans are depicted as rows of small black outlines, packed floor to ceiling, side by side, and head to toe. This image was used in flyers, posters, and public lectures.

Photo by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

Commemorative Coins

The exhibition showcased two small commemorative coins, one for William Wilberforce, labelled “The Friend of Africa,” and one for Thomas Clarkson, identified as President of the 1840 Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Their ideas, once resisted, became the moral backbone of a nation’s conscience. The coins speak to legacy: what we choose to remember and why it matters.

Photo by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge.

Final Reflections

Walking through this exhibition, one could not help but feel the weight of history, not just in ink and paper, but in ethical decisions, public courage, and long persistence. Every artefact connected academic inquiry to political action, personal risk to public memory. That St. John’s College, once the training ground of both Clarkson and Wilberforce, was the setting for this exhibition made it all the more powerful. We left not simply informed, but moved. Because ultimately, this was more than a tour, it was a reminder that history doesn’t belong behind glass. It demands to be seen, heard, and carried forward.