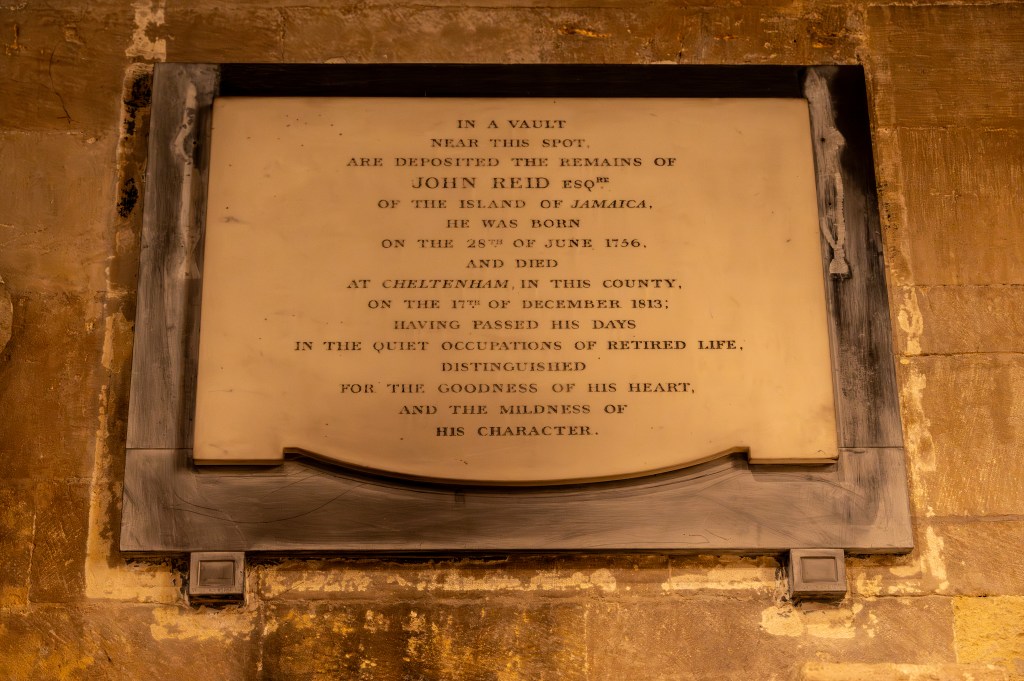

TABLET INSCRIPTION

Location: Tewkesbury Abbey, East Wall,

IN A VAULT

NEAR THIS SPOT,

ARE DEPOSITED THE REMAINS OF

JOHN REID ESQRE

OF THE ISLAND OF JAMAICA,

HE WAS BORN

ON THE 28TH OF JUNE 1756,

AND DIED

AT CHELTENHAM, IN THIS COUNTY,

ON THE 17TH OF DECEMBER 1813;

HAVING PASSED HIS DAYS

IN THE QUIET OCCUPATIONS OF RETIRED LIFE,

DISTINGUISHED

FOR THE GOODNESS OF HIS HEART,

AND THE MILDNESS OF

HIS CHARACTER.

Chapel of St John Baptist and St Catherine.

John Reid, 1756-1813.

By Sarah Crowe

John Reid was born on the 28th of June 1756 in Jamaica, and died in Cheltenham on the 17th of December, 1813.1 He was the son of John Reid and Mary Haughton (who came from the same plantation-owning Haughton dynasty as Lady Ann Clarke – see below) and his brother, George Reid senior, owned a neighbouring estate to John’s called “Friendship.”2 John Reid left “all his personal estate” to his wife (also called Mary), apart from his “slaves, cattle, stock […] belonging to Wakefield estate,” which he placed in trust so that she had income from them.3 John’s father Colonel John Reid, also referred to in documents as John Reid senior (d. 1777) owned Long Pond estate in Jamaica, contributing funding from the estate to the University of Pennsylvania.4

John Reid’s wife, Mary Haughton Reid died in Liverpool in 1847 and was, in her own right, the owner of Hermitage Settlement.5 She was compensated for 135 slaves in 1832 – a total claim amounting to £2460 7s 7d, as were many other slave owners at this time due to the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.6 The link between the Reid and the Haughton families can be seen through the lineage of Philip Haughton (1700-1765), and marriages between the two families, for example between “Thomas Reid of Bunkers Hill” and “Elizabeth Haughton James” who were married in Hanover, Jamaica, on the 8th of September 1778.7 Philip Haughton had daughters Mary and John Reid’s “relation” Ann (who he is described as being interred near later in this document – see also the research document on Ann Clarke).8 Philip Haughton’s will states, regarding his daughters Ann and Mary:

To my daughter Mary James and her heirs lawfully begotten 1/2 of the sugar plantation called Green Island including 1/2 the land I purchased adjoining the estate which formerly belonged to William James deceased and was sold by virtue of a writ of extend and purchased by me from Kames Kerr and 1/2 the slaves, 24 mules and 40 working steers. To my grandson Philip H. JAMES the other 1/2 at 21 and £100 a year till then. Also to Mary James a piece of land patented by William Pusey containing 540 acres, a piece patented by Michael Corney containing 575 acres, and 2 runs patented by William DORRELL of 600 acres and 1/3 of the negroes and stock belonging to my penns. To my daughter Ann Clarke my sugar plantation called Fat Hog Quarter with 60 acres I purchased of John Heath, all the negroes thereupon and 24 mules and 40 steers. Also to Ann Clarke the parcel of land known as the Cockoon containing an estimated 2100 acres to the eastward of the land I purchased from William Tharpe and ½ of the slaves and stock belonging to my penns.9

UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British Slavery.

There are numerous examples in the contemporary press of Jamaican goods and ships crossing from Jamaica to Britain in the late eighteenth century from the Reid estates, as well as newspaper articles outlining details of the estates themselves which sometimes mentioned the enslaved people owned by the Reid family. Examples of “Reid” owned ships which featured in press articles from the time include the “Jamaica Frigate, Reid, bound from Jamaica for London” which was reported on in the press in 1757 and a ship called “the Old Harbour, Reid, from Jamaica,” which was driven ashore in Hearn Bay due to bad weather in 1760.10 The Star (London) under the heading “From Lloyd’s List,” appears to document what appears to be Reid’s emigration from Jamaica to Britain, as it describes as having “arrived – at Liverpool, John, Reid, from Jamaica” in 180211 In the same year, On the 28th of August, the Royal Cornwall Gazette reported as “Arrived,” in its column titled “From the Jamaica Papers,” the “ship John, Reid, from Gold Coast. With 280 slaves.”12

In 1794 the Royal Gazette of Jamaica reported that a slave named “Hardtimes, a creole man-boy, belonging to Wakefield estate, Trelawney,” (John Reid is demonstrated to have owned this estate at this time) was, “In Hanover Workhouse, Sept. 23, 1794.”13 An enslaved person was likely to have been in the workhouse at this time most often as a form of punishment, for example for running away, while being held for sale, or to be “broken in” when they first arrived on the island.14 Conditions in Jamaican workhouses were horrific.15

The Gloucester Journal carried John Reid’s death notice, stating, “died, at Cheltenham, John Reid, Esq. of St Julia’s Cottage, aged 57 […] on Friday he was interred near his relation, Lady Clerck (sic), in Tewkesbury Church.”16 The Cheltenham Chronicle, reporting his death in December 1813, stated “the private character of this gentleman was truly amiable, possessing of every essential which could render him a desirable associate to his equals, and combining the enviable qualities of benevolence and condescension to his inferiors. He departed this life universally beloved, & equally lamented.”17 The Chronicle then also describes him as being interred “near his relation Lady Clerck” before listing the mourners, which included an un-named “Haughton, Esq.”18 There is property by the name “St Julia’s Cottages” listed in the 1855-1857 Cheltenham Old Town Survey, which concurs with the Cheltenham Chronicle article above which states says that he was “of St. Julia’s Cottage, in this town.”19

The examples in the press provided here of enslaved people and goods produced by them being brought to Britain on John Reid’s ships and the treatment of those people in Jamaican workhouses as detailed above are starkly juxtaposed to the wording in his death notice in the Cheltenham Chronicle, which suggests he was “truly amiable” and “exhibited benevolence and condescension” during his life, leading him to be “universally beloved and equally lamented.”20 The fact that these two aspects of his life are so jarring when presented side by side is a compelling example of the importance of nuanced research into complicated public figures of the time such as John Reid.

- Tewkesbury Monuments Review.pdf, John Reid, <https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q76315271.>

[accessed 10/4/2025]. “Mr J Reid” is listed among the numerous “arrivals during the week” into Cheltenham September, 1811, 161 Cheltenham Chronicle, 19 September, 1811, <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000311/18110919/005/0003> [accessed 24/3/2025]. ↩︎ - John Reid of Wakefield Estate and Cheltenham, UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British

Slavery, <https://wwwdepts-live.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146650267/> [accessed 10/4/2025]. Wakefield, Windsor Research Centre, <https://www.cockpitcountry.com/wakefield.html#:~:text=Wakefield%20Estate%20originally%20belonged%20to,Reid> [accessed 10/4/2025]. George Reid Senior, UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British Slavery <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/-1349901499> [accessed 10/4/2025]. Friendship, Windsor Research Centre, <https://www.cockpitcountry.com/friendshipreids.html> [accessed 10/4/2025]. Friendship [1], UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/37> [accessed 10/4/2025]. Reid’s from Sheffield Westmoreland Belmont Jamaica West Ind, Genealogy.com,

<https://www.genealogy.com/forum/regional/countries/topics/jamaica/6614/> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - John Reid of Wakefield Estate and Cheltenham, UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British

Slavery, <https://wwwdepts-live.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146650267/> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - John Reid senior of Long Pond, UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British

Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146650269> [accessed 10/4/2025]. Mary Haughton Reid, Find a Grave, <https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/271371496/mary-reid> [accessed 10/4/2025], and The Long Pond Great House, <https://thelastgreatgreathouseblog.wordpress.com/tag/william-reid/> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Mary Haughton Reid (nee James), UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British

Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/12162> [accessed 10/4/2025]. Hermitage Settlement, UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/1513> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Mary Haughton Reid, Find a Grave, <https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/271371496/mary-reid>

[accessed 10/4/2025]. Jamaica Westmoreland 684 (Hermitage Settlement), UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/claim/view/12092> [accessed 10/4/2025]. Slavery Abolition Act, Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Slavery-Abolition-Act>, [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Thomas Reid of Bunkers Hill, UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146664915#:~:text=Biography,Bunkers%20Hill%20%5BNovember%201794%5D> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Philip Haughton, UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146638937> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Philip Haughton, UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146638937> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Newcastle Courant, 19 of November 1757,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000085/17571119/013/0002> [accessed 24/3/2025]. Sussex Advertiser 29 December 1760, <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000260/17601229/002/0002> [accessed 24/3/2025]. ↩︎ - Star (London), 4 December 1802,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002646/18021204/009/0003> [accessed 24/3/2025]. ↩︎ - Royal Cornwall Gazette, 28 August 1802,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000682/18020828/009/0002> [accessed 24/3/2025]. ↩︎ - Royal Gazette of Jamaica, 4 October 1794,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002834/17941004/097/0032> [accessed 24/3/2025]. Wakefield estate: Wakefield, UCL Centre for Study of the Legacies of British Slavery <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/2186> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Marcia Mayne, A Visit to the Hanover Museum, Jamaica, Inside Journeys, 28 January 2013,

<https://insidejourneys.com/a-visit-to-the-hanover-museum-jamaica/#:~:text=There’s%20another%20large%20room%20but,the%20overseer%20who%20stood%20nearby.&text=One%20disturbing%20artifact%20that%20is,during%20the%201760%20Tacky%20rebellion> [accessed 10/4/2025]. The Slave Workhouse, Cambridge University Press, <https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/all-for-liberty/slave-workhouse/53B83C88BEF4A8C8D591E46CF8027D2C> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Marcia Mayne, A Visit to the Hanover Museum, Jamaica, Inside Journeys, 28 January 2013,

<https://insidejourneys.com/a-visit-to-the-hanover-museum-jamaica/#:~:text=There’s%20another%20large%20room%20but,the%20overseer%20who%20stood%20nearby.&text=One%20disturbing%20artifact%20that%20is,during%20the%201760%20Tacky%20rebellion> [accessed 10/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Gloucester Journal, 3 January 1814,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000532/18140103/013/0003> [accessed 24/3/2025]. ↩︎ - Cheltenham Chronicle, 30 December 1813,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000311/18131230/011/0003> [accessed 24/3/2025]. ↩︎ - ibid. ↩︎

- 1855-1857 Cheltenham Old Town Survey, <http://cheltlocalhistory.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/OTSIndex.pdf> [accessed 10/4/2025]. Cheltenham Chronicle, 30 December 1813,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000311/18131230/011/0003> [accessed 24/3/2025]. ↩︎ - Cheltenham Chronicle, 30 December 1813,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000311/18131230/011/0003> [accessed 24/3/2025]. ↩︎