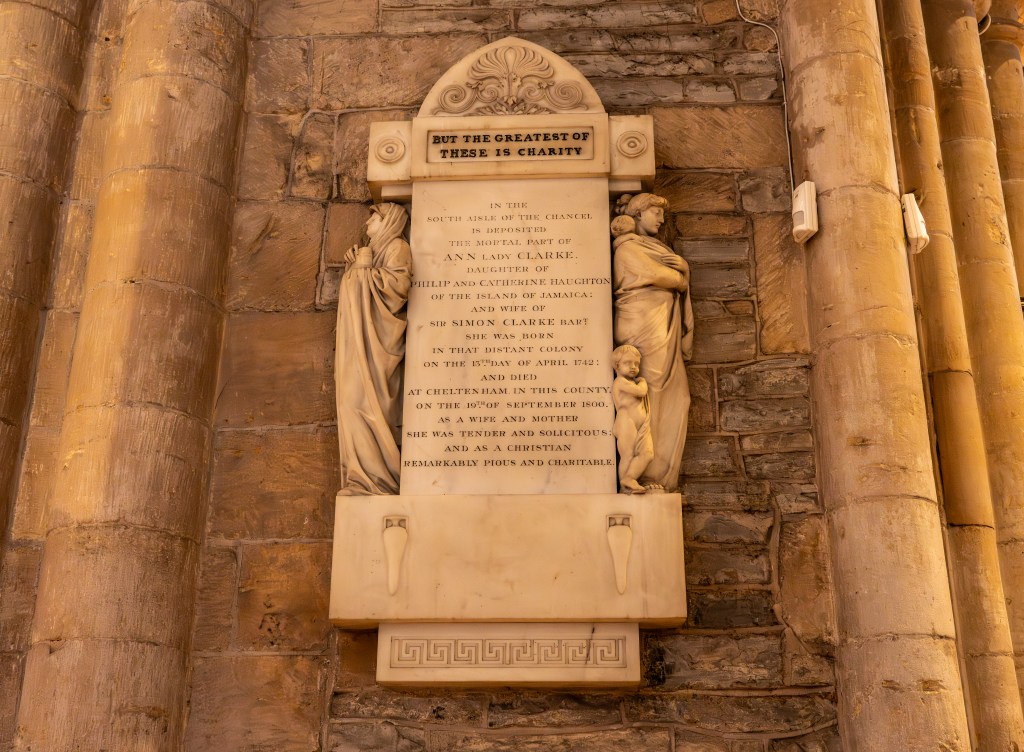

STONE TABLET INSCRIPTION

Location: Tewkesbury Abbey, North Wall of the North Choir Aisle,

BUT THE GREATEST OF

THESE IS CHARITY

IN THE

SOUTH AISLE OF THE CHANCEL

IS DEPOSITED

THE MORTAL PART OF

ANN LADY CLARKE.

DAUGHTER OF PHILLIP AND CATHERINE HAUGHTON

OFF THE ISLAND OF JAMAICA:

AND WIFE OF

SIR SIMON CLARKE BART.

SHE WAS BORN

IN THAT DISTANT COLONY

ON THE 13TH DAY OF APRIL 1742

AND DIED

AT CHELTENHAM IN THIS COUNTY.

ON THE 19TH OF SEPTEMBER 1800.

AS A WIFE AND MOTHER

SHE WAS TENDER AND SOLICITOUS:

AND AS A CHRISTIAN

REMARKABLY PIOUS AND CHARITABLE.

between the North Transept and the Arch that is over the shop.

Lady Ann Clarke, 1742-1800.

By Sarah Crowe

Ann Haughton (1742-1800) and her husband Sir Simon Clark, 7th Baronet (1726-1777), were members of two of the wealthiest and most influential plantation-owning families in Jamaica, both families spanning several generations on the island.1 Ann was the “daughter and co-heiress of Philip Haughton. She married Sir Simon Clarke, 7th Bart., [on the] 21/07/1760 [and] inherited Fat Hog Quarter and Cocoon Castle Pen from her father in 1765.”2 Ann’s will stated that she:

charged her estate with £22,000 for the benefit of her daughter Catherine Haughton Clarke on condition she waived her right to the Retirement estate, which went to her [the testatrix’s] son Sir Simon Haughton Clarke. She left £1500 to Philip Clarke the reputed son of her late son Sir Philip Haughton Clarke. After other monetary legacies of £1000 to her husband’s family she left her residual estate to Sir Simon Haughton Clarke.3

UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery.

Ann’s father, Phillip Haughton, was the “son of Jonathan Haytayne (baptised 1667 in Barbados) and Mary nee Dehany of Vere and the Owner of Fat Hog Quarter and Green Island in Hanover.”4 In his will, he bequeathed to Ann:

my sugar plantation called Fat Hog Quarter with 60 acres I purchased of John Heath, all the negroes thereupon and 24 mules and 40 steers. Also to Ann Clarke the parcel of land known as the Cockoon containing an estimated 2100 acres to the eastward of the land I purchased from William Tharpe and ½ of the slaves and stock belonging to my penns.5

UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery.

He was buried in Fat Hog Quarter (referred to as Hog Quarter) having died in 1765 at the age of 64.6

In turn, Ann and Simon’s son, Phillip Haughton Clarke, the 8th baronet, inherited land and enslaved people in Jamaica from his parents.7 This included the Warwick Castle estate on Jamaica and its more than 300 enslaved people.8 Ann’s daughter was born on Jamaica in 1773, lived in England and had at least seven sons.9 Ann and Simon’s grandson, the 9th Baronet, was one of many individuals (along with the relatives of other individuals researched for the Tewkesbury Project – please see their separate research documents), who claimed compensation for enslaved people that he owned in the 1830s due to the Abolition of Slavery Abolition Act, 1833.10

Ann’s husband Sir Simon Clarke’s family had lived in Jamaica for generations – his father’s cousin Sir Simon Peter Clarke, 5th baronet, was transported there in 1731 for committing a highway robbery in 1730.11 His conviction and subsequent transportation was reported on in many newspapers at the time.12 Sir Simon Clarke 6th Baronet inherited the baronetcy from his cousin the 5th baronet upon the latter’s death in 1736 without issue.13 The 6th baronet became a prominent slave and plantation owner on the island, and his son the 7th baronet – Ann’s husband – inherited these properties.14 Goods and vessels from their estates can be seen being reported on as they made their way to different ports, for example in 1747 a ship in his family’s name can be seen In the Pennsylvanian Journal in an entry in the “custom-House, New-York” section, where the vessel in the name of “Clarke, to Jamaica” was “cleared for departure.”15

There were very few newspaper references to Lady Ann Clarke or her husband, 7th Baronet Sir Simon Clarke. It would appear that Ann “arrived at Cheltenham Spa” in August 1800, a month before her death in September of that year.16 Unlike in the case of, for example, Henry Fowke, who can be seen to be an active and respected member of society in and around the Tewkesbury area, there was no reporting on similar local good works carried out by the Clarkes in Jamaica or Britain, and references, which were discovered of them tended to be with regards their goods or vessels, or references to their many estates.17 The reason for Ann’s memorial in Tewkesbury Abbey appears to be solely due to her being a relative of John Reid (who was descended from another prominent plantation-owning dynasty – see the research document on him), who lived in Gloucestershire. Several newspapers reporting on the death of John Reid in 1813 commented on the fact they were related, for example, the Gloucester Journal carried John Reid’s death notice, stating, “died, at Cheltenham, John Reid, Esq. of St Julia’s Cottage, aged 57 […] on Friday he was interred near his relation, Lady Clerck (sic), in Tewkesbury Church.”18

Ann was descended from a line of plantation owners called the “Hawtaynes/Hawtains/Hawtons/Haughtons” (there are several spellings of their surname) and a marriage between the Haughtons and the Clarkes ultimately linked two of the most well-known plantation-owning families on the island. Ann’s niece carried on the tradition of marrying into/merging prominent slave-owning families, as in 1794, “Benjamin Lyon, esq. of the island of Jamaica” married “Miss Begg, niece to Lady Clarke, of the same island.”19 The Lyon family were, along with the Clarkes, Haughtons and Reids, another prominent plantation-owning family on Jamaica.20

In May 1795 the Clarke’s Jamaican estates were mentioned in an advertisement in The Times for the exhibition “Views in the Island of Jamaica, Delineated by Mr. Hamilton” which featured a “view of a living bridge upon Lady Clarke’s estate, nr. St. Lucra, formed by the famous Banyon Tree across a river.”21 This exhibition also included “Two Negro Dances”; one of them consisting of 150 portraits in the dresses in which they appeared on Christmas Holidays,1793.22

Ann’s death was announced in the Bath Journal on the 29th of September 1800, which simply stated “At Cheltenham, Lady Clarke, of Gloucester-Place, Portman-Square, relict of the late Sir Simon Clarke, bart. of Jamaica.”23 In 1857 the numerous Haughton-Clarke family estates and many hundreds of acres and parcels of land on Jamaica can be seen being put up for sale, “late the property of Sir Simon Haughton Clarke,” through a London solicitor.24 There was a general decline in the sugar trade at this time, (as it began to be eclipsed by coffee) which was exacerbated by the abolition of the slave trade, necessitating the sale of many of these estates.25 However, as with the other families, which have been researched for this project, the Haughton-Clarkes could be seen to have benefitted from the profits from these estates, and the suffering of the people enslaved on them, for many generations.

- Sir Simon Clarke 7th Bart., UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146646377#:~:text=In%20his%20will%20made%20and%20proved%20in,Long%20Pond%20be%20suspended%20until%20his%20son> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Lady Ann Clarke (nee Haughton), UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146638949> [accessed 15/4/2025]. Further details of Fat Hog Estate can be found here: Fat Hog Quarter Estate, UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/3144> [accessed 15/4/2025] and here: Philip Haughton, Cumberbatch Family History, <https://cumberbatch.org/genealogy/getperson.php?personID=I86&tree=tree1> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - “Lady Ann Clarke (nee Haughton),” UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146638949> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - “Philip Haughton,” UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146638937> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - ibid. Enoch Hobart appears to have been her father Phillip’s business partner – his private papers,

including correspondence with Phillip Haughton, are held here: “Enoch Hobart Papers, 1754-1766,” <https://nlj.on.worldcat.org/search/detail/47279516?queryString=kw%3A%28phillip%20haughton%29%20AND%20%28yr%3A1700..1800%29&databaseList=2237%2C2259%2C2260%2C2261%2C638&origPageViewName=pages%2Fadvanced-search-page&clusterResults=true&groupVariantRecords=false&expandSearch=true&translateSearch=false&queryTranslationLanguage=&lang=en-GB&scope=> [accessed 15/4/2025]. There is more biographical information on Phillip here: Philip Haughton Snr, Family Search, <https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LHKY-7QR/philip-haughton-snr-1700-1765> [accessed 15/4/2025]. Family Tree of Sir Philip Haughton Sr, <https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Haughton-438> [accessed 15/4/2025]. “Philip Haughton,” <https://www.geni.com/people/Philip-Haughton/6000000188559947821> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Fat Hog Quarter, Find a Grave, <https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2803328/fat-hog-quarter-estate> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎

- Philip Haughton, Cumberbatch Family History,

<https://cumberbatch.org/genealogy/getperson.php?personID=I86&tree=tree1> [accessed 15/4/2025]. Sir Philip Haughton Clarke 8th Bart., UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146638977> [accessed15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Warwick Castle Estate, UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/1947> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Catherine Haughton Clarke, Family Search, <https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LVFW-V6C/catherine-haughton-clarke-1773-1808> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎

- Sir Simon Haughton Clarke, 9th baronet, The National Gallery,

<https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/people/sir-simon-haughton-clarke-9th-baronet#:~:text=Slavery%20connections,Jamaica%2C%20with%2083%20enslaved%20people> [accessed 15/4/2025]. Slavery Abolition Act, Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Slavery-Abolition-Act>, [accessed 10/4/2025]. Ann and Simon’s children can be found listed here: Sir Simon Clarke, 7th Bart., <https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q75584756> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Sir Simon Clarke 6th Bart., UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146638939#:~:text=Biography,assistance%20in%20compiling%20this%20entry> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Kentish Weekly Post 10 March 1731,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003200/17310310/002/0001> [accessed 15/4/2025]. Newcastle Courant, 6 February 1731, <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000085/17310206/008/0003> [accessed 15/4/2025]. Caledonian Mercury 24 December 1730, <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000045/17301224/005/0003> [accessed 15/4/2025]. Kentish Weekly Post, 17 March 1731, <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003200/17310317/004/0002> [accessed 15/42025]. ↩︎ - Sir Simon Clarke 6th Bart., UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146638939#:~:text=Biography,assistance%20in%20compiling%20this%20entry> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - ibid. ↩︎

- Pennsylvania Journal, 24 February 1747,

<https://www.newspapers.com/image/1033750012/?match=1&clipping_id=169979828> [accessed 15/4/2025]. There were many references to ships in the name of Clarke sailing to and from Jamaica at this time: Western Flying Post, 24 January 1757, <https://www.newspapers.com/image/979347922/?match=1&terms=Clarke%20Jamaica%20> [accessed 15/4/2025] and Derby Mercury, 21 January 1757, <https://www.newspapers.com/image/394349353/?match=1&terms=Clarke%20Jamaica%2020> [accessed 15/4/2025] contain just two examples. ↩︎ - Gloucester Journal, 18 August 1800,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000532/18000818/030/0003> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Manchester Mercury, 1 February 1774,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000239/17740201/005/0002> [accessed 15/4/2025]. “Hog’s head” barrels of sugar, as mentioned in this article are explained here: Shipping Sugar, Encyclopaedia Virginia, <https://encyclopediavirginia.org/12862-> [accessed 16/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Gloucester Journal, 3 January 1814,

<https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000532/18140103/013/0003> [accessed 24/3/2025]. ↩︎ - Chester Chronicle, 26 September 1794,

<https://www.newspapers.com/image/786203274/?match=1&clipping_id=169980050> [accessed 15/4/2025]. The link between the Clarkes and Beggs can also be seen here: Sir Simon Clarke 6th Bart., UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146638939#:~:text=Biography,assistance%20in%20compiling%20this%20entry> [accessed 15/4/2025]. And here: Simon Fleming Begg, UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146660035> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - James Lyon, UCL, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery,

<https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146650131#:~:text=Biography,half%20of%20James%20Lyon’s%20estate> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - The Times, 20 May 1795,

<https://www.newspapers.com/image/32896482/?match=1&clipping_id=169918811> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - ibid. ↩︎

- The Bath Journal, 29 September 1800, p. 2,

<https://www.newspapers.com/image/976175412/?match=1&terms=Sir%20Simon%20Clark> [accessed 9/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Morning Chronicle, 10 August 1857,

<https://www.newspapers.com/image/392657754/?match=1&clipping_id=169980238> [accessed 15/4/2025]. The Times, 22 June 1857, <https://www.newspapers.com/image/33059976/?match=1&clipping_id=169980286> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎ - Sidney Mintz , “Labor and Sugar in Puerto Rico and in Jamaica, 1800-1850” Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Mar., 1959), pp. 273-281 <https://www.berose.fr/IMG/pdf/labor_and_sugar_in_puerto_rico_and_jamaica-177876.pdf> [accessed 15/4/2025]. ↩︎